Northern Front

For the invasion of Russia, code-named ‘Operation Barbarossa’, the German Army assembled some three million men, divided into a total of 105 infantry divisions and 32 Panzer divisions. There were 3,332 tanks, over 7,000 artillery pieces, 60,000 motor vehicles and 625,000 horses. This force was distributed into three German army groups: Army Group North, commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, had assembled his forces in East Prussia on the Lithuanian frontier. His Panzergruppe, which provided the main spearhead for the advance on Leningrad, consisted of 812 tanks. These were divided among the 1, 6 and 8.Panzer-Divisions, 3, 36.Motorised-Infantry-Division and the SS.Motorised-Division ‘Totenkopf’, which formed the Panzergruppereserve.

Among the strong force of Army Group North, the Gebirgsjäger were to play a major part in the battle in the East. For the invasion, the 2 and 3.Gebirgs-Divisions, which were part of the Gebirgs-Korps, were allocated in the Gebirgs-Korps Norwegen.

During the early morning of 22 June 1941, the mountain troopers attacked Russia and followed in the wake of the leading spearheads of the mighty Panzerwaffe. On the northern front, the terrain was terrible, comprising of swampland, barren rock and huge dark forests. The area was regarded as so bad that even the local Finns could not believe they were conducting operations in such an inhospitable place. But, despite the appalling conditions and the long marches, they smashed through Soviet defences and reached the River Liza in July 1941. By this time, the Russians had been totally shattered by the weight and accuracy of the German shellfire but also by the skilful deployment of the Gebirgsjäger storm troops.

However, in spite the rapid drive of the German soldier into Russia, the Red Army were a complete enigma to him. There was little information supplied about the country in which they were invading, nor was there anything substantial on the terrain and climate. He simply saw the Russians as Slavic people that were an inferior race. Propaganda had made good use to prove conclusively that all Russians were living in poverty and its antiquated army were totally unprepared for war. Even when the German soldier rolled across into Russia, during the summer months of 1941, he was totally unaware of the immense undertaking he had in crushing the enemy. Although the ordinary German found a huge contrast between his own country and that in which he was fighting, they were totally unprepared for the unimaginable size and distance in which they had to march. The soldiers were amazed by the immense forests, the huge expanses of marshland, and the many rivers that were continuously prone to flooding. They were also surprised that the little information they did have, was often incorrect. Maps frequently showed none of the roads, and when they were fortunate enough to come across them, they were in such terrible state of repair that military traffic would often reduce them to nothing more than dirt tracks.

Gebirgsjäger forces march across into the Soviet Union with Army Group North during the summer of 1941. Among the strong force of Army Group North, the Gebirgsjäger were to play a major part in the battle in the East. For the invasion, the 2 and 3.Gebirgs-Divisions, which were part of the Gebirgs-Korps, were allocated in the Gebirgs-Korps Norwegen.

The roads were appalling in Russia and were often unable to cope with the large volumes of traffic. After a downpour of rain, the roads, which were no more than dirt tracks, were turned into a quagmire, even during the summer period in the north. Here, in this photograph, Gebirgstruppen, with their pack animals towing supplies, trudge through the mud towards the front.

From a hill top and Gebirgs officers can be seen observing enemy positions. By their position, there appears to be some danger of enemy fire. Note the officer wearing a leather greatcoat watching the forward movement of his troops through a pair of 6×30 field binoculars.

Another great contrast that the German soldier experienced during his march through Russia was the climatic conditions. There were extreme differences in temperature, with the bitter cold sometimes dropping to thirty or even forty degrees below zero, and the terrible heat of the summer when temperatures soared to insufferable levels. When the first snow showers arrived, in October 1941, the German soldier was totally unprepared for a Russian winter. Sleet, and the cold driving rain, turned the Russian countryside into a quagmire with roads and fields becoming virtually impassable. The lack of winter clothing too, caused widespread worry for the soldiers, for they knew that the winter would create graver problems than the Russians themselves.

Living and fighting in the winter on the Eastern Front was very difficult, even for the well trained men of the Gebirgsjäger. The distances the soldiers had to travel were immense. The most popular form of transport was by sledge. Sheltering, too, posed a huge problem and many of them were taught to construct native style shelters from tree branches and build igloos. Although these mountain forces sustained heavy casualties during the winter of 1941, they grimly held the line, and by early 1942, a stalemate developed. Before the spring, only minor skirmishes continued, as both sides rebuilt their strength.

In early spring 1942, the 7.Gebirgs-Division was deployed far north, as the Soviets unleashed their new offensive. For weeks and months, the mountain troops fought a battle of attrition, trying to prevent the Soviets cutting them off. A series of vicious Russian assaults nearly succeeded, but the arrival of bad weather, once again, deprived the Red Army of victory. By the time the bad weather had improved, the Gebirgsjäger had brought up additional reserves and equipment. The Russian offensive failed and the mountain troopers were able to spend the next two years, until 1944, patrolling the northern sector.

In the summer of 1944, the Red Army launched another offensive on the Northern Front. The attack was so fierce that the Finns concluded a separate peace with the Russians, in September 1944. With the prospect of being cut off, all German troops, including those of the Gebirgsjäger, were pulled back through Lapland into Norway, whilst at the same time combating Norwegian troops who had now turned against them.

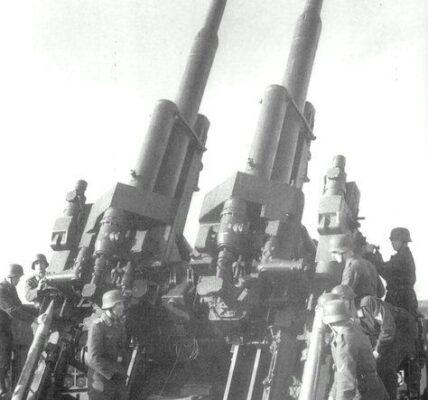

Overlooking the Baltic coast is a 2cm FlaK 30 anti-aircraft gun. This FlaK gun weighed some 770kg and had an effective ceiling range of 2,200 meters against aerial targets. In the Gebirgsjäger, these guns were operated by light flak companies and were used extensively to protect both mountain troops and Wehrmacht forces against enemy aerial attacks. They could also be used in a ground defensive role too, with great effect.

Southern Front

On the Southern Front, mountain troops saw more extensive action against the Red Army than those operations conducted in the north. In June 1941, the 1 and 4.Gebirgs-Divisions were involved in the rapid advances which followed the invasion of Russia. The soldiers covered some 35-miles each day and maintained this truly remarkable progress, day after day, week after weary week. During these early days, morale was high. They smashed through the Stalin Line and conducted vigorous attacks deep into enemy territory. They had also participated in the encirclement of the Uman pocket, which saw 100,000 Red Army troops being marched into captivity. The Gebirgs-Korps alone captured 22,000 prisoners. This, in itself, was a great victory and for weeks and months that followed, the mountain troops pushed further east towards Stalino, which was captured in November 1941. They then advanced to positions by the River Mius where winter was fast approaching.

In July 1942, the Gebirgsjäger took part in the drive on the Caucasus Mountains. It was here that the soldiers were able to exhibit their Alpine skills and scale some of the highest peaks in the Caucasus range. On Mount Elbrus, they managed to plant the German national flag. By the end of 1942, as the city of Stalingrad was about to fall, the 1 and 4 Gebirgs-Divisions were withdrawn, barely escaping the clutches of the Red tide. Both divisions halted at the Kuban bridgehead, where they fought until the autumn of 1943, in mosquito-infested marshland.

Three photographs, taken from the same slide, showing SS-Division Nord during action against enemy positions in a wooded area. The division saw action on the Norwegian–Finnish border and began hostilities against the Russians, in June 1941, in an Operation, code-named ‘Arctic Fox’. During a battle at Salla, against strong Russian forces, Nord suffered 300 killed and 400 wounded in the first two days of the invasion.

At the end of the year, the 5.Gebirgs-Division was withdrawn from the Leningrad sector where it saw extensive action on the Southern Front. But, despite the stiffening of German forces in the south, nothing could prevent the growing strength of the Soviet Army. By early 1944, over four million Russian soldiers were now being thrown at the exhausted troops. Even the elite Waffen-SS Gebirgs-Divisions could do nothing to stem the rapid enemy onslaught. By mid-May, the Red Army overran the Crimea and was remorselessly bearing down on the Carpathian Mountains.

The end in the East seemed imminent. Hitler began taking drastic steps to try and hold the Russians from overrunning the Hungarian oilfields. To bear the brunt of this massive defence strategy, the 1. Gebirgs-Division, now attached to parts of the 2.Panzer-Armee, took part in the offensive around the area of the Platensee.

On 5 March 1944, the attack began in earnest, but the spring thaw turned the countryside into a sea of mud and almost immediately the troops of the 2.Panzer-Armee were bogged down in the mire. As for the Gebirgsjäger, they could still move with their pack animals, and, during the first ten days, they made good progress. But then their advance ground to a halt. Along the disintegrating German front, a mere handful of units, including the 1.Gebirgs-Division and the 13.Waffen-Gebirgs-Division der SS ‘Handschar’, mainly composed of Bosnian Moslems, faced a massive Russian Army of some 40 divisions. Under the pulverizing effects of the Russian troops and their artillery, both the 2.Panzer-Armee and the 6.SS.Panzer-Armee were forced to withdraw. As the bulk of the German forces retreated under a hurricane of fire, it was up to the 1.Gebirgs-Division to fight back the Soviet force whilst the remnants of the Wehrmacht clawed its way westward.

Gebirgstruppen from the new SS-Division Nord during operations in the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. A motorcycle combination is following a Pz.Kpfw.II towards the battlefront watched by soldiers on the edge of the road. SS Kampfgruppe Nord was formed in February 1941, from two SS Totenkopf Regiments. The designation changed to SS-Division Nord in September 1941, and again in September 1942, to SS Gebirgs-Division Nord, and finally to 6th SS Gebirgs-Division Nord.

Nord truppen in action with their 3.7cm PaK35/36. Even though the PaK35/36 had become inadequate for operational needs, in the face of growing armoured opposition, they were still quite capable of causing some serious damage to their opponent.

A Nord MG34 machine gun crew with their weapon attached to a Lafette 34 sustained-fire mount with optical sight. Note the special pads on the front of the tripod. These were specifically used when the weapon was being carried on the carriers back. The pads would allow the carrier some reasonable comfort.

Here, Gebirgstruppen hold a morning formation inside a Russian village. They are all wearing the standard Gebirgsjäger uniform. Once their commander had finished lecturing his men, the troops would disperse and prepare for their daily duties in the snow. This would first consist of the soldiers donning their winter camouflage smocks and standard field equipment.

Three photographs showing a Gebirgsjäger wearing the special woolen toque beneath the Bergmütze. Typically, troops wore two toques in the extreme arctic conditions, as these photographs vividly illustrate. One was worn over the head to protect the ears and face, and one around the neck. The toques main purpose was intended to keep the head warm whilst wearing the steel helmet, which during winter operations in the east, the soldiers referred them as like a ‘freezer box’. Along with the toque, the soldier either wore the winter white camouflage smock or the standard issue greatcoat with insulated two-finger mittens.

Five photographs showing an SS-Division Nord ski patrol during operations in Army Group North, during the winter of 1942. They are all wearing the early winter camouflage smocks over their uniforms and fur covered head-dress. The fur covered caps were issued to German troops serving in the East during the winter of 1942. Most of the men are carrying over their shoulder the Kar98k carbine bolt action rifle, which was distributed to all infantrymen during the war. Of particular interest, many of the ski troops can be seen wearing the coloured friend-or-foe recognition stripes on both sleeves.

Inside a Russian village and a Gebirgsjäger award ceremony is being undertaken. The soldier on the left, wearing a whitewashed M35 steel helmet, holds the rank of an Oberleutnant and congratulates a Leutnant on his award of the Iron Cross 2nd Class.

Three Gebirgs soldiers pause in their march following a ski patrol. During the snow months in Russia, especially during the second winter period, the new practical loose-fitting hooded snow overalls were worn, purely designed to wear over many layers of clothing, including the greatcoat. These men are wearing thick woolen gloves and a woolen toque for the head. Two of the men wear tinted ski goggles over their Bergmütze field cap. They are armed with the 7.92mm Mauser Gew33/40 rifles, which were slightly shorter than the standard Kar98k carbine.

Gebirgs soldiers using a sled to move from one part of the front to another. Even by 1942, the majority of motive power within the regiments of the infantry divisions was mainly animal draught. As a consequence, many hundreds of thousands of horses died either due to combat action, or succumbed to the extreme weather, lack of forage, or were eaten by starving soldiers.

Gebirgstruppen approach a forest in deep snow during operations on the Ostfront in 1942. Signs of enemy movement were often easier to identify in the snow, and a vigilant patrol could quickly detect the location of their enemy by fresh foot prints and snow knocked off bushes and other disturbed foliage.

A mountain trooper on a ski patrol. He wears the standard issue Gebirgs rucksack, which appears to be heavily laden with supplies. In order to camouflage him in the snow he wears the snow overall. The snow overall was large and shapeless and worn without a belt over any of the uniform and all equipment. However, in spite of being produced in high numbers to the Gebirgsjäger, this item of clothing did not prove to be as practical as other camouflage smocks, as it tended to restrict the wearers freedom of movement.

An MG34 machine gun squad advance through a wooded area to a new firing position. They wear the two piece snow suit and white washed M35 steel helmets. In snow, soldiers found it necessary to apply white paint over the steel helmet. Initially, during the first winter of 1941, many troops did not attempt to apply their steel helmets with any type of white camouflage, often leaving them in the field-grey. However, some did attempt to find a solution in order for them to blend in with the local terrain. A number of soldiers found that chalk was very useful and applied this crudely over the entire helmet. But it was whitewash paint that became the most widely used form of winter camouflage.

Weary infantry rest in a wooded area and try to sleep in the snow after enduring probably many days of bitter fighting against stiffening Russian resistance. The troops are compelled to protect themselves against the bitter temperatures with Zeltbahn shelter-quarters. Foliage from the surrounding pine trees would also have been used as bedding to keep the men dry. For the German forces on the Eastern Front there was little respite – if the Red Army let up for a brief period, the sub zero temperatures certainly did not.

Supply vehicles for Gebirgsjager and Wehrmacht front line troops have halted on a congested road. During the winter on the Ostfront, wheeled forms of transportation were frequently immobilised due to the extreme weather conditions. Consequently, this would hamper supplies to the front line and occasionally bring an advance to a stall.

For local defence, an MG34 machine gun is seen mounted on an anti-aircraft tripod mount. Throughout the war, support units were issued with light machine guns for self-defence and were able to counter low flying enemy aircraft quite regularly. The Gebirgs machine gunner wears the animal skin fur coat, issued for use to German troops driving vehicles or on guard duties on the Eastern Front during the winter.

A well camouflaged Pz.Kpfw.III has halted on a congested road. One of the crewman watches a long column of Panjewagens pass by. These troops are part of the SS Gebirgs Division Nord, and are more than likely transporting divisional rations and equipment to frontline troops.

Two photographs showing two different artillery observation posts using the 6×30 Sf.14Z Scherefernrohr or scissor binoculars, searching for enemy targets. Each artillery battery had an observation post among the frontline positions. However, in extreme arctic conditions, the lenses sometimes iced over, hampering the surveillance of the frontlines.

Two photographs, taken in sequence, showing a 7.5cm Geb36 gun being loaded and then fired by its well trained crew. Firing an artillery piece in the snow could be frequently problematic for the gun crew. The recoil would regularly drive the weapon deep into the snow and would often cause inaccurate firing. For this reason, a number of gun crew sometimes modified their 7.5cm Geb36 gun, removing its wheels and replacing them with sturdy gun trails.

Two Pz.Kpfw.II’s can be seen passing pioneers attached to the SS Gebirgs Division Nord, in 1942. The area can be seen totally devastated by either heavy artillery or air bombardments. Whilst this type of tactical bombardment served the Germans well, during the winter the lack of shelter was often problematic for the soldiers.

Soldiers of the SS Gebirgs Division Nord stand beside two stationary Pz.Kpfw.II tanks during operations on the Kestenga front. The soldier standing to the left of the motorcyclist, who is wearing the special motorcycle protective suit, appears to be armed with a captured Russian 7.62mm Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 rifle. The Germans designated this Soviet weapon as the Gew252(r).

A convoy of supply trucks carrying men and equipment has halted along a road. Some of the mountain troops have dismounted from their vehicles and are seen standing near a stream. It is more than probable that this is a temporary stop and the column would have resumed its drive.

Soldiers of the 6.SS-Division-Nord in one of a number of shelters erected along the stagnate front. Although such shelters did not provide much, in terms of protection to the men against enemy fire, they certainly provided the soldiers with adequate shelter against the bitter elements.

A road march, during the summer of 1943, in Army Group South. The pack animals are well laden with equipment and a number of them can be seen attached with basket carriers, which were commonly used by the Gebirgsjäger to carry their rations and other vital supplies needed to sustain them in some of the most inhospitable places on the Ostfront.

An interesting photograph showing a Gebirgs Artillery unit on a long march. One of the pack animals can be seen towing a 7.5cm GebG36, which was the standard artillery piece used by the mountain troops during the war in the East.

Apart from towing ordnance, the pack animals were also well adapted for carrying artillery. Here, in this photograph, pack handlers and their animals rest before resuming their march. A 7.5cm GebG36 has been broken down into eight loads for transportation. Note the mule carrying the spoke wheels for the gun.

Two mountain troop motorcyclists can be seen with their BMW motorcycles in a stream, cleaning their dusty vehicles. By this period of the war, many of the motorcyclists were used for dispatch purposes to various sections of the front, and because motorcycles were regarded as versatile machines, it enabled them to move swiftly across terrain with important information.

Two troop leaders can be seen halted on a road with their unit. The troop leader, wearing his M35 steel helmet and 6×30 field binoculars, wears the 1st pattern MP38/40 magazine pouches for his MP38/40 sub-machine gun. By 1941, the MP38/40 sub-machine gun was manufactured in great numbers, and issued to squad leaders, senior NCOs and front line officers.

A Gebirgs FlaK 30 gun in an elevated position. The guns usual shield has been removed, probably to lighten the weight. Normally, the shields were used when the gun was being utilized against a ground target.

A group of mountain troops push a sanitation vehicle up a steep gradient. It is unlikely that any of these men are part of the medical personnel, except one seen wearing a white overall. Normally, all medical aide-men wore the Red Cross on a white armband.

Out in a field and the crew of a 7.5cm GebG36 are seen poised in a field with their gun in an elevated position. Note, the Gebirgs crew wearing the silver Jäger cap badge of three oak leaves and an acorn as worn by Jäger-Divisions.

Three photographs showing a Gebirgsjäger taking aim with his carbine 98K bolt action rifle. He wears the camouflage wind jacket which was similar in design to that of the Waffen-SS camouflage smock. It was made of waterproof fabric, and he is seen here wearing white-side out. The other side of the jacket was printed in three colours, similar to that of the Wehrmacht splinter jacket.

Five photographs showing Gebirgs troops during operations on the Ostfront. As with many Gebirgsjäger units during winter operations, they are using animal draught to tow sleds full of supplies. Although the Gebirgsjäger continued to fight hard to hold their positions, they were constantly subject to intense bombardments by whole divisions of Soviet artillery. Difficulties of terrain, too, hindered communications between the units, especially in the snow. One of the quickest and effective methods of moving from one part of the front to another was either by ski or sled.

A ski patrol can be seen moving towards some high-ground. Shelter for the soldiers was often at a premium, especially when evacuating a position. Quite frequently, out in the snow, soldiers were compelled not only to build various forms of shelter to combat the arctic temperatures, but to protect themselves against enemy fire.

Two commanders scrutinize a map during defensive operations in Army Group South. The officer on the right is wearing another variety of animal skin fur coat. His comrade wears the familiar white camouflage smock and can clearly be seen wearing the coloured friend-or-foe recognition stripe on his sleeve.

A snow ski patrol prepares to leave camp. The two ski soldiers nearest to the camera are wearing the shapeless two-piece snowsuit comprising of a snow jacket and matching trousers. The jacket was buttoned all the way down the front with white painted buttons. It had a large white hood, which could easily be pulled over the steel helmet. The hood not only helped conceal the headgear if it had not already received any type of winter covering, but also afforded protection to the back of the wearer’s neck and to the ears. The trousers were also shapeless and were tucked into the boots.

Gebirgstruppen march in close formation across the snow. Without their white camouflage smocks these soldiers would have undoubtedly been vulnerable to enemy air attack. Close formation marching like this was commonly used by the Gebirgsjäger, especially in arctic weather conditions where the soldiers would be able to stay in close proximity to each other, especially in low visibility.

Ski troops transport an injured comrade on a sled to a makeshift field hospital. Living and fighting in sub-zero temperatures was very difficult for the Germans, even for hardened veterans fighting their second winter in Russia. In a number of areas, in Northern Russia, wheeled transport was generally useless in the trackless wastes and forests, and often the most effective means of transport was the sled.

Gebirgs soldiers supported by animal draught advance along a road. A supply vehicle can be seen passing the column.

Mule drawn If.8 infantry carts of the 1.Gebirgs-Division can be seen crossing a stream. Note the reluctant bull attached to the cart. The 1.Gebirgs-Division fought on the southern flank of the Eastern Front, fighting at Kiev, Stalino, the Dnepr crossing, and Kharkov, before moving into the Caucasus during Operation Blau. After the defeat at Stalingrad, it spent time in Greece and Serbia before retreating to Austria, until it finally surrendered.

Weary and exhausted Gebirgstruppen during their withdrawal through southern Russia, in the late summer of 1943. After the defeat at Stalingrad, the 1 and 4 Gebirgs-Divisions were withdrawn, barely escaping the clutches of the Red tide. Both divisions halted at the Kuban bridgehead where they fought until the autumn of 1943 in mosquito-infested marshland.

Two photographs showing the terrible road conditions endured on the Eastern Front, in the autumn of 1943. Two vehicles and a motorcyclist from the 1.Gebirgs-Division struggle through the mire after a heavy downpour of rain. Roads in the Soviet Union were few, and cross-country travel often caused its own problems. Coupled with the sheer size of the country, the Russian weather offered the invaders considerably greater challenges than on any other front during the war.

Pack mule handlers rest with their animals. The vast distances in which these animals and their handlers had to travel can well be imagined. Typical Russian steppes comprised of nothing but vast expanses of flat terrain, stretching for as far as the eye could see. Due to the visible landmarks, units were often unable to determine their exact location.

A long column of mule pack handlers with their animals trudge along a muddy road, passing stationary vehicles and a motorcycle that has obviously developed a mechanical problem. The mules were versatile and sturdy animals and often endured painful long marches with little provision. Note the special canvas tarpaulin covers to protect the pack-loads.